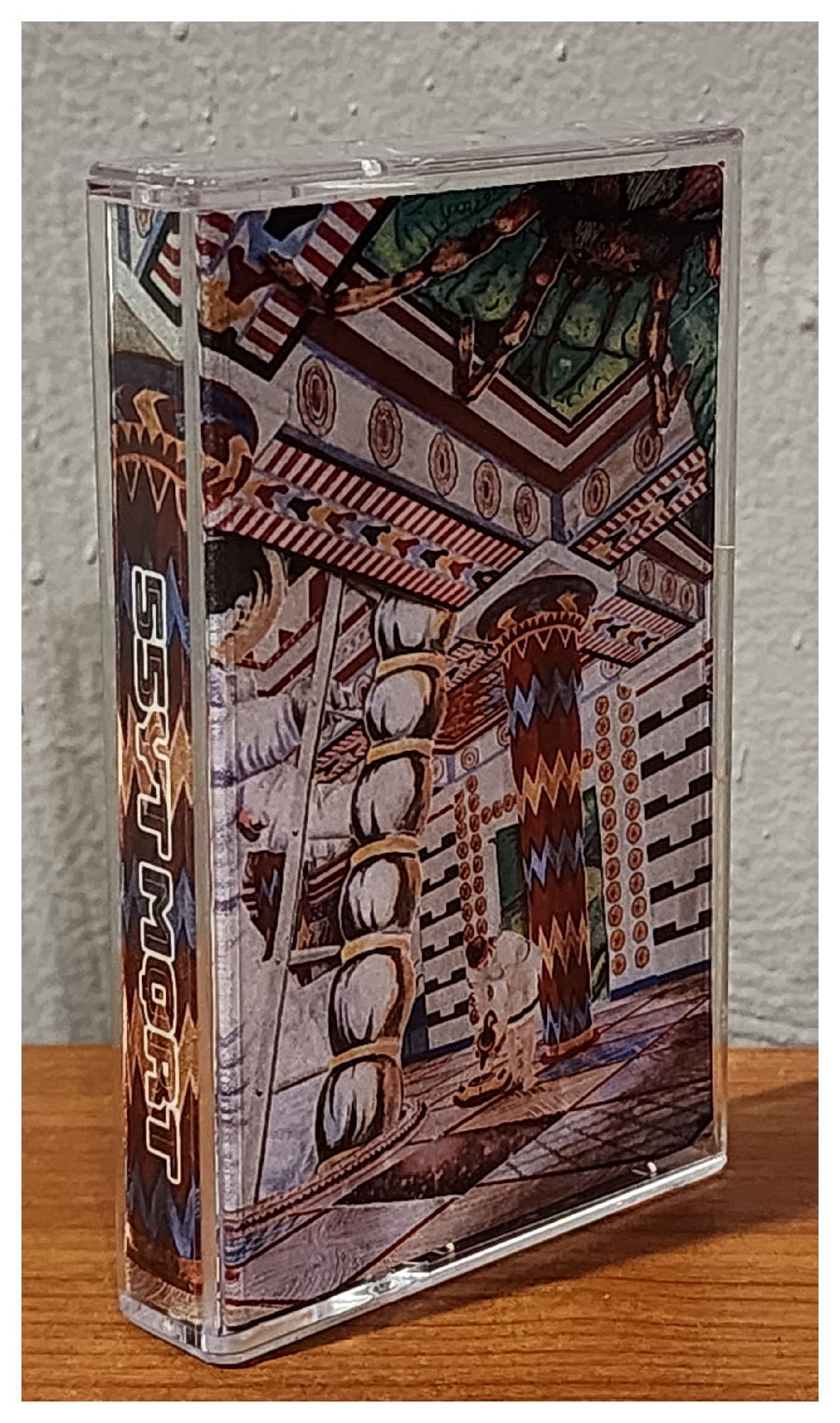

55YT MQRT was formed in Redwood City, CA way back in 2006. At that point in time, my friend Neal Jensen and I were high schoolers deep diving into the world of psychedelic and progressive rock, our favorites being The Mars Volta, Pink Floyd, and King Crimson. We had just left our post-hardcore outfit Ending Reason and we very much wanted to explore some more experimental sonic territory ourselves.

We originally formed under the name Hellships. For reasons unknown to me now, we ended up dropping that name and instead chose to go by 55YT MQRT. Something about progressive rock that has always made us laugh is how often people complain that bands within the genre are “pretentious,” so we chose a name that we found maximally pretentious as a way to poke fun at the people who make such complaints. (Neal later ended up properly forming Hellships in Olympia, WA with Robin Flowers and Alex Freilich. I produced their two studio albums, Leaden Hum and Doom Organs in 2012 and 2015 respectively. I consider Hellships and 55YT MQRT to be sibling projects… Hellships is a bit more of an unhinged and “off the grid” fellow, whereas 55YT MQRT is an equally strange individual who somehow manages to hold down an office job.)

We developed the band’s compositional approach in the early days. We would do long improv sessions that were then edited down in Pro Tools into seamless songs. From there we would add elements, cut parts, and rearrange things until the songs felt complete. We released our early tracks on MySpace.

Within a year of forming the band, Neal moved to Olympia, leaving our project with an uncertain future. In 2010 I ended up deciding to move there as well. We became roommates and revived 55YT. We assembled an untitled album consisting mostly of ambient noise tracks. When we moved from our apartment into a house where we could make loud music, we started properly practicing again. Over the next roughly 4 years we would occasionally work on 55YT material, but during that time we did not properly record anything due to focusing on other projects (Hellships, A God or an Other, Bird Surgeon, The Lunch).

Neal eventually decided to move to Montana to pursue a master’s degree, and again this left the band with an unknown future. In January 2016, before he left, we decided to properly document what we had been working on, again following the edited improv approach of our early works. We quickly had solid recorded versions of our songs that represented what we had been doing live during that time: Neal playing a single guitar accompanied by myself on the drums. The lone overdub was bass for fullness. Neal then left for Montana. This version sounded complete to me, but not to Neal. He wanted to overdub some additional parts he had been imagining.

He came to visit Olympia and we recorded his extra ideas. Now that there were additional elements on certain scattered parts, the parts with no overdubs sounded empty to me! And thus, a nearly 8 year process began. Parts were added and edits were made in short bursts, usually when Neal would come to visit for a few days here and there. Sometimes the session sat for literally years without being opened. Finally, in November 2023… we knew it was complete.

It shocks me when I think of how different my personal world and even the world in general was when we began working on this album. I was pursuing music full time living in Washington state. Donald Trump was just beginning his first run and the idea of him becoming president was ludicrous. Since then, I moved halfway across the country, had a son and a daughter, worked as a cable technician for 4 years, and made my jump into software development as a career. And the whole pandemic thing happened.

This is my longest-running recording project to date. I don’t know how many people will connect with this album but this is one of my personal favorite releases I’ve ever put out. We had been envisioning creating something like this since high school. The vision is finally fulfilled.

Over the last couple of years Neal has regularly been coming from Iowa, where he currently resides, to visit our family in Colorado. During those visits we have been recording new tracks which will be the basis for the next 55YT MQRT album. If the pattern holds, we’ll release the next album somewhere around 2031. We’ll see!

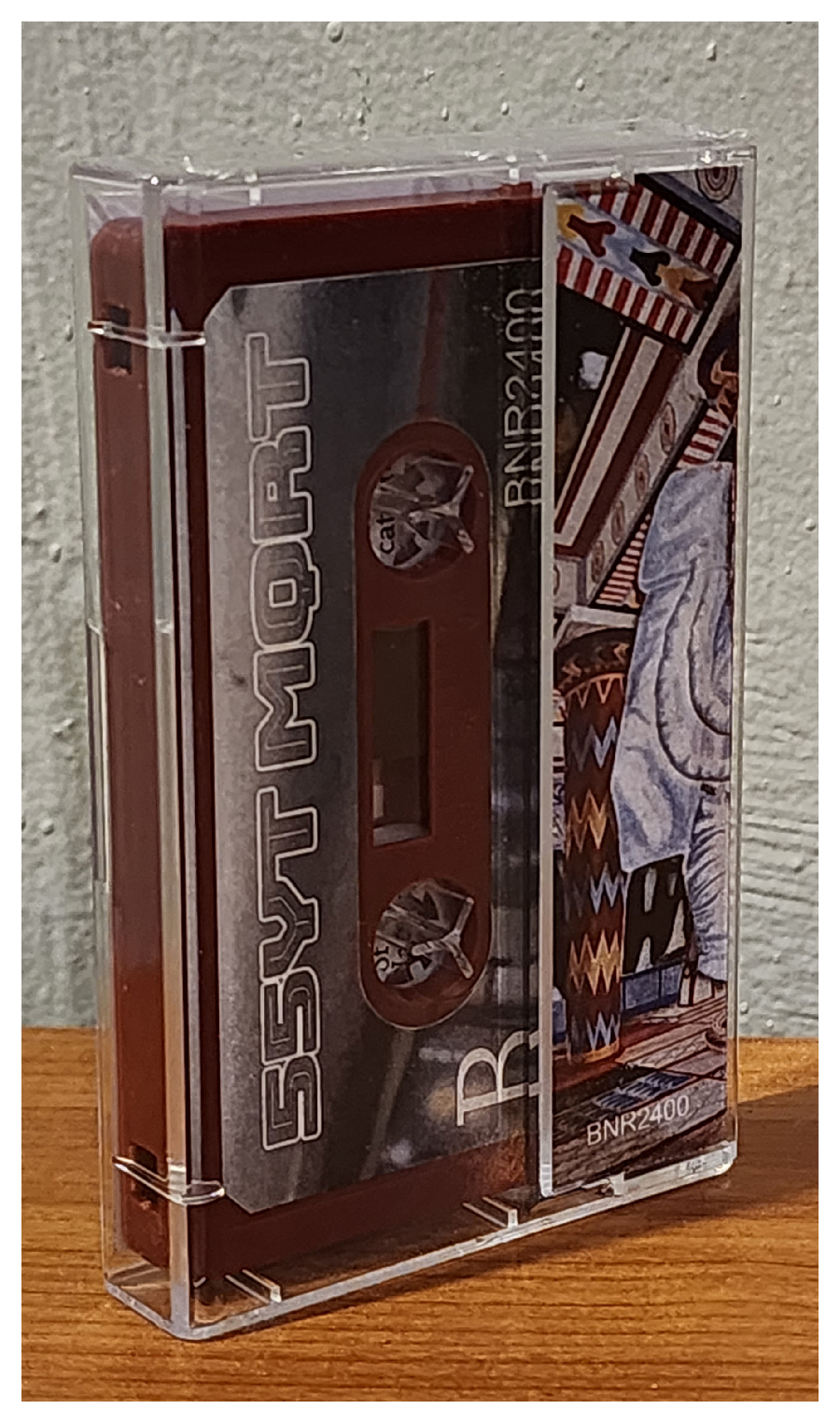

Album art by Garrett Botkins.

Gapless w/ Lyrics on YouTube:

Stream or Download/Purchase (name-your-price) on Bandcamp: