Party Apartment – Eyes closed to the sun

Tracked, edited, mixed, and mastered at Big Name. This song is the third in a series of teasers for an upcoming full length.

Party Apartment – Eyes closed to the sun

Tracked, edited, mixed, and mastered at Big Name. This song is the third in a series of teasers for an upcoming full length.

To someone familiar with my solo releases, it might seem strange that this one has been put out under the same moniker as my album [visitor]. The two releases are almost diametrically opposed in terms of sound, but in my mind, they clearly belong to the same project.

What determines if something is [syzygy]? The project’s driving question is: “What can I do with only this?”

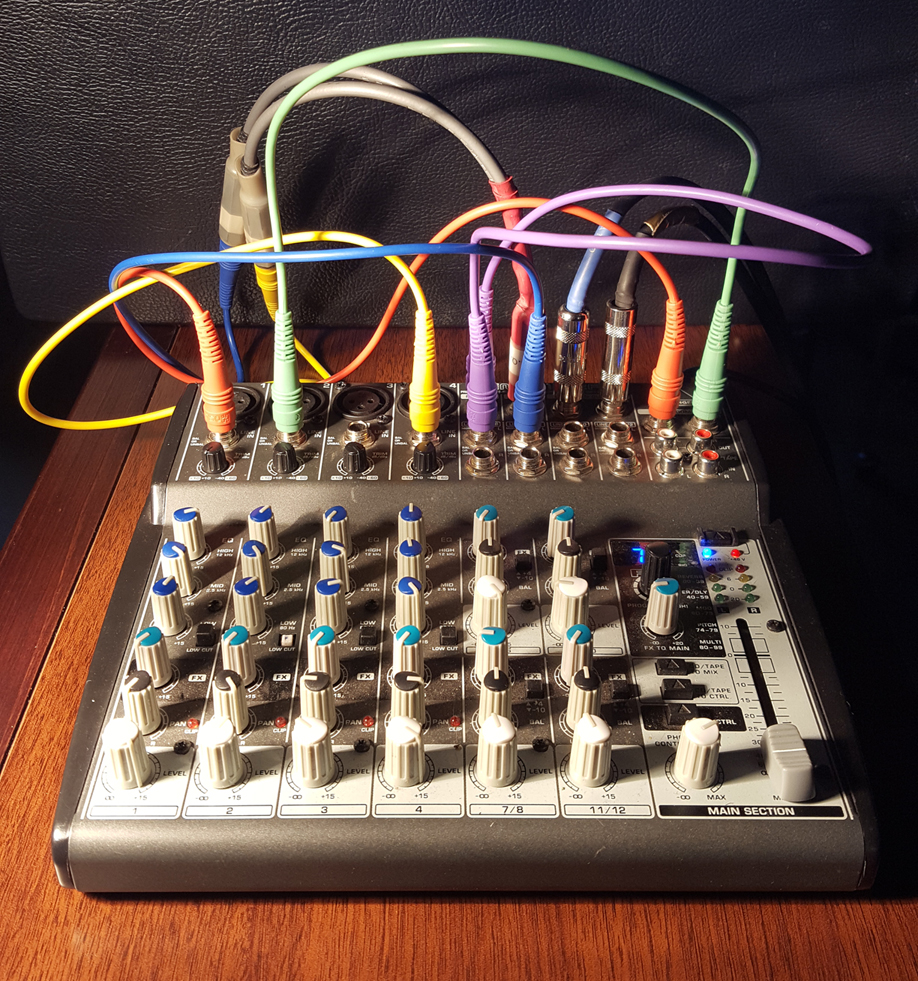

In the case of [visitor], the “only this” is my detuned, 80-year-old spinet piano and my fretless electric bass. In the case of [ouroboros], it is my Behringer Xenyx 1202 mixing board.

All of the sounds that are heard on this release were generated by only a mixing board. This was accomplished by routing the various outputs of the mixer back into the various inputs on the mixer, creating internal analog feedback loops. This is known as the “no-input mixer” technique.

It’s a deceptively simple tactic. Though it seems like it should result in basic, abrasive feedback squelches, the reality is much cooler. The various signal routings through the mixing console interact with one another to create surprisingly complex waveforms.

Each mixer generates sounds unique to its hardware. This is one of the only situations I can think of where lower quality gear can have a huge advantage over higher quality gear: lower quality components tend to modify the waveform passing through them more than higher quality components do. As a result, when the waveforms sum back together, they coalesce into more chaotic wave-interference patterns (i.e. feedback loops).

Behringer is known for making gear focused more on economy than quality, so the Xenyx 1202 is perfect for this application. When you really crank the signals with this thing, especially the low frequencies, it overloads and creates fantastic drum-machine-like rhythms. It can also generate single notes that sound like an electronic synth, as well as more noisy blocks of sound. Hidden within it, I’ve found sounds reminiscent of motorcycles racing through tunnels, ringing analog phones, air raid sirens, scurrying mice, alarm systems, heavy machinery, ray guns, heartbeats, woodblocks, flutes, and much more. This device has a very dystopian palette.

The composition process:

This is probably the only session I have done so far where I actually utilized the sound of a brickwall limiter as an effect. I use limiters on every session that I master, as well as on select parts of certain mixes, but I usually attempt to keep them as transparent as possible. These songs have the limiter set far beyond the normal levels I tend to use. This smashes the layers together, causing the tonal layers to take on the rhythmic characteristics of the noise layers underneath them.

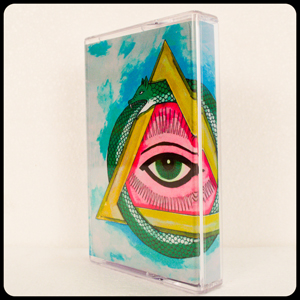

Its inscription reads, “One is the Serpent which has its poison according to two compositions, and One is All and through it is All, and by it is All, and if you have not All, All is Nothing.”

While working on this project, I was struck by the idea that the no-input mixer is a sonic embodiment of the ouroboros: the snake that circles around, consuming its own tail. This symbol is ancient. It is first known to have been used in the 14th century BCE, and has been used by a plethora of spiritual traditions since.

Carl Jung said, “The Ouroboros is a dramatic symbol for the integration and assimilation of the opposite, i.e. of the shadow. This ‘feed-back’ process is at the same time a symbol of immortality, since it is said of the Ouroboros that he slays himself and brings himself to life, fertilizes himself and gives birth to himself. He symbolizes the One, who proceeds from the clash of opposites, and he therefore constitutes the secret of the prima materia which… unquestionably stems from man’s unconscious.”

The ouroboros symbolizes the universe’s nature of continual creation, destruction, and recreation. Its constant reinvention. The paradox of the non-conflicting dual nature of all things. The hidden oneness of the seeming duality between physical and mental worlds. The infinite. The shadow within.

I enlisted my partner Laura to paint the art and I think the piece is exactly right for the music. This isn’t related to the album, but as a side note, she’s currently doing an awesome 100-piece Instagram series of scenes and objects found around our house. It can be found at instagram.com/ladylervold. Check it out and give her a follow if you like what you see.

Final Notes / Other

One thing that I particularly enjoyed experimenting with while creating this recording was its inherent microtonality.* None of the notes on this recording were created using fixed pitch keys like you find on a keyboard. The no-input mixer is capable of producing an infinite range of pitches. Since I was free of 12 tone equal temperament tuning, I was able to step back and simply use my ears to find harmonies and chord progressions that I enjoyed without being stuck inside the rigid 12tet realm. The other side of the inherent microtonality of this process is found in the base layer in each song. When the mixing board develops complex waveform patterns, it doesn’t use any tuning theory. The harmonies it generates are pure physics and mathematics, and the intervals it spits out are not bound to 12 tone equal temperament tuning.

The other aspect that I really enjoyed playing around with while working on this was the appearance of high-denominator odd-meter rhythms (for example: 27/32). These are rhythms that can only be notated by using 32nd or 64th notes. You don’t often hear them in music because they are very difficult for humans to play accurately, especially at high speed. Complex feedback, however, has no aversion to them, so a lot of them ended up in the final compositions here.

Released on Big Name Records – BNR1702

Available on cassette via the Big Name Records Webstore or Bandcamp.

Cassettes were printed in the Big Name print shop.

Party Apartment – Gasoline (and the smell of it)

Both songs tracked, edited, mixed, and mastered at Big Name. These songs are teasers from a full length to be released later this year.

9 tracks (38 minutes) of blackened death crust. Tracked, edited, and mixed at Big Name. Mastered by Brad Boatright at Audiosiege.

The song “Pass Me the Yogurt Chips Before I Cremate Myself, Emilio” from my/Joel/Steve’s album Retail Monkey – ADD/Nihilism was just featured on the fifth edition of Can This Even Be Called Music?’s compilation series. This comp doesn’t focus on a specific genre, just great stuff that the creator enjoys.

This is the second installment of my new Instagram multipanel-video series. These are quick original compositions that have no restriction on genre or instruments used.

This sentence is a link to my Instagram account. If you like what you see, please feel free to hit that follow button.

AOL 3.0 – June 5, 2017

Not yet in Your Closet Hiding From an Enraged Yo-Yo Ma – June 8th, 2017

The Curling Champion of the World – June 16th, 2017

The View Was Pretty Nice up There, on the Roof of Arby’s – June 22nd, 2017

Clean Your Teeth on My Bones – June 27th, 2017

Boy Rex (Jack Senff) recorded his debut, self-released album The Bloodmonths here at Big Name in early 2016. Since then, he moved to Michigan, got signed, recorded a new album, and began pursuing touring as Boy Rex full time. I was pleased to welcome him back to Big Name to do this stripped down live-in-studio session as a stop on his current tour.

Okay, so this piece is going to take some time to explain because it combines some uncommon experimental composition ideas. So to make things short for those who don’t want to read something long and dry, I will begin by putting this in quick-and-dirty terms:

Point 1 is particularly oversimplified. So if you’d like a more detailed, accurate representation of what this is, read on.

A few months ago, I released Key West, an algorithmic/microtonal* piece that was composed using the awesome software known as Pure Data. While I really enjoyed how that piece turned out, I wanted to go further with Pure Data and create something that had stronger rhythmic content. Within a few days of completing it, I began putting together a new composition.

I put quite a few hours into it over the next few weeks. The code ended up a lot more complicated than I expected. I liked how it all came together, but upon finishing it… I felt that I couldn’t put it out yet. This was because I actually didn’t understand some of the theory behind what I had done, and didn’t know how I was possibly going to explain it. I was told that to someone who wasn’t already deep into lunatic-fringe musician territory, the explanation I wrote up for Key West was mostly incomprehensible gobbledygook, so I wanted to be sure that I could thoroughly explain this new one before I put it out to the public. I had to do some research to figure out what exactly I had come up with.

Like Key West, this piece also experiments with microtonality. Most music that we hear is written in 12edo (equal division of the octave), which splits the octave into 12 notes that the human ear interprets as even jumps in pitch. Key West utilizes a temperament known as 5edo, where the octave is split into 5 notes that the human ear interprets as even jumps in pitch, allowing the utilization of notes that are not found in most music.

This song, however, abandons that approach and uses a different kind of system. The composition came to be as a result of my curiosity regarding different ways of splitting up the octave. After trying a bunch of different things, I happened to take the octave and split it up into 16 even divisions… but instead of splitting them up in equal cent intervals (tones that the human ear interprets as even jumps), like with an EDO, I split the octave evenly in hertz (i.e. vibrations per second). This is one of the things that I did that, at the time, I didn’t fully understand, and later got really confused by, so hopefully I can explain.

The human ear interprets frequencies logarithmically. Doubling any frequency will result in an octave harmony. We understand 200hz to be the same note as 100hz except one octave higher. This doubling continues with each iteration of the octave; 400hz, 800hz, 1600hz, et cetera are all perceived as the same note. This means that in a tuning system where every step of the scale is interpreted by the ear as being exactly even, the amount of Hz between each note increases.

So, as I said before, I derived the scale that I used for this piece in the opposite way. Instead of dividing evenly in cents, I divided the octave evenly into Hz. This means that as the scale increases, the ear interprets the intervals as getting closer together. I later learned that this is known as an otonal scale due to its relation to the overtone series (shout-outs to Dave Ryan and Tom Winspear for helping me figure out what the heck this approach is called).

This particular scale is known as otones16-32. From my research, otonal scales seem to be pretty uncommon. I don’t know why that is. They’re a very logical way to construct mathematically harmonious scales. To my ear, they can be utilized in a way which sounds very consonant, but they also allow for some exotic xenharmonic flavor.

From the 16 available notes in this scale, I chose a set of 7 of them that I thought sounded agreeable together. The ratios† of these notes are:

I found the sound of this scale inspiring (especially when I heard how strange it sounded to build chords with it), so I set out to put together a new algorithmic piece. Like I said earlier, I wanted to be more ambitious and give the thing more structure than my last effort.

An algorithmic composition, in its simplest form, is music that is made by creating and then following a set of rules. The term, however, is more commonly used for music where the artist designs some kind of framework (most often a computer program) that allows the piece to perform itself without intervention from the artist. In this case, I did just that: coded a framework of rules dictating which sounds are generated when by a combination of soundwave generators.

This composition also falls under a closely related musical form known as generative music. A composition is generative if it is unique each time that it is listened to. It needs to be continually reinventing itself in some way. This algorithmic composition is also a generative composition because the computer makes many determinations about the musical output each time that it is played. Every time the program runs and the song is heard, the chord progressions are different, as are the rhythms and notes that the instruments play. Many aspects of the composition are the same each time, but many others are determined by the computer and are unique to every listen.

There is one aspect of the composition that I listed under the “rules I chose” heading that I would actually consider some kind of middle ground: the available chord progressions. While I was working on coding the program, I made a chord progression generator. It automatically created bar-long chord progressions. Each time it would generate a loop, I would listen to it a few times and decide if I liked it or not. If I liked it, I would add it to the list of progressions that the computer could choose from. The ones that were musical nonsense were deleted. About 1/3 of the progressions generated by the algorithm I designed were usable. So in the end, I did choose the chord progressions that were included. But the computer created them in the first place.

On a different note, this method of presentation of the piece raises some art philosophy questions. Is the YouTube video of the piece being played actually the same piece? It’s not truly representative of the generative nature of the song; the YouTube video will be exactly the same every time it is played. It’s a facsimile that only demonstrates one particular runthrough. Eventually I’d like to make the jump over to Max/MSP, an extremely similar visual coding language that allows you to compile your code into a standalone program that anyone can run.

Lastly, all of the sounds you hear in the piece are generated via what is known as waveform synthesis. They are created by adding various combinations of sine waves and white noise‡ to one another. This creates complex waveforms which our ears interpret as different timbres. I could write a post entirely about how the sound generators in this piece work together to create the sounds that you hear, but this post is already long enough. Maybe for my next Pure Data based composition, I will focus my explanation entirely on that aspect of the piece.

Yikes! That’s a lot longer than I expected. Hopefully someone finds this interesting. At the very least, writing this cemented a bunch of this stuff in my brain.

The Clavins – File Corruption EP: Unfinished Instrumentals

Here’s a post unlike any other on my blog! I didn’t produce this music at all. Steve (one of my favorite people for 15ish years and co-writer of ADD/Nihilism) made these rad songs and used my piece Steve from the Repeating Features series as the cover art. Check it out!

Earlier today, The Hard Times (specifically, author Kyle Erf) put up an absolutely savage satire piece about noise artists. I’m a huge fan of THT’s work, so I decided to spend a little time today blurring the lines between joke and reality by making a Bandcamp for the band that they invented in the article.

The supposed band consists of members Hans Lederman (drums) and Ashleigh Milton (production) of New York City. Collectively they are known as Antiverb. Their release, General Purpose, is a 7″ disc of 180-grit sandpaper intended to be played on a turntable.

I was greatly amused by both the article and the EP’s concept, and upon completing my reading wondered if anyone had gone to the trouble of fleshing out the non-existent release. I entered “antiverb.bandcamp.com” in my address bar and found that no such page existed. “Antiverb band” on Google yielded no results either. I was honestly shocked that no one was using that name. At that moment I knew: I had to be the one to do it. I had to make this Bandcamp for the sake of the few other weirdos in the world who would read that article and think, “I wonder if anyone has made this into a Bandcamp.”

Anyway, to begin the process, I recorded the sound of a piece of sandpaper on a turntable. As someone who does a lot of work on my house, I happened to have it lying around, so I didn’t even need to hit Home Depot. Score.

As you can see in the video, the needle doesn’t move laterally while the sandpaper spins; it just sits in one position. This means that the sandpaper “record” would play continually until stopped by the listener. A computer program could be coded to replicate this endlessness, but Bandcamp only operates with standard audio files. An audio file can’t be infinite, so the digital recording of this EP needed a chosen length. The article states that the release is a 7″, so I decided to make the digital version 6 minutes long, as this is approaching how long a single side of a traditional 7″ record can be.

After recording and mastering the audio, I registered the Bandcamp page and uploaded the track. At this point I had to decide what to add for other content. I wanted to fill in as many of the fields as possible with information derived from the article. For the “about” section I took the brilliant Harold Zhou “New York Times” review that mentions using the EP to prep a shelf for staining. The artist bio was similarly taken from Lederman’s quote about the intent of the project.

For the credits, the band members’ names and roles were simple enough to fill in. The digital version really was recorded at Big Name, so I put that in there too. At this point I had exhausted the supply of pre-existing ideas. It was time to come up with some original content to fill out the rest of the page.

I used my scanner to scan more of the sandpaper that I had lying around. I was really worried about scratching my scanning bed, but as far as I can tell I got away with it. This scan was used for the album cover as well as the Bandcamp’s header and background. Next, for the artist photo, I used a picture of myself and Laura. I modified the image so our faces don’t show (so it’s not clearly just us) and then I added an overlay using the sandpaper I had just scanned because I thought that was funny.

The article mentioned a label releasing the EP, but did not give that label a name. So I had to come up with one. I chose Acquired Distaste Records; it just strikes me as a perfect noise-label name.

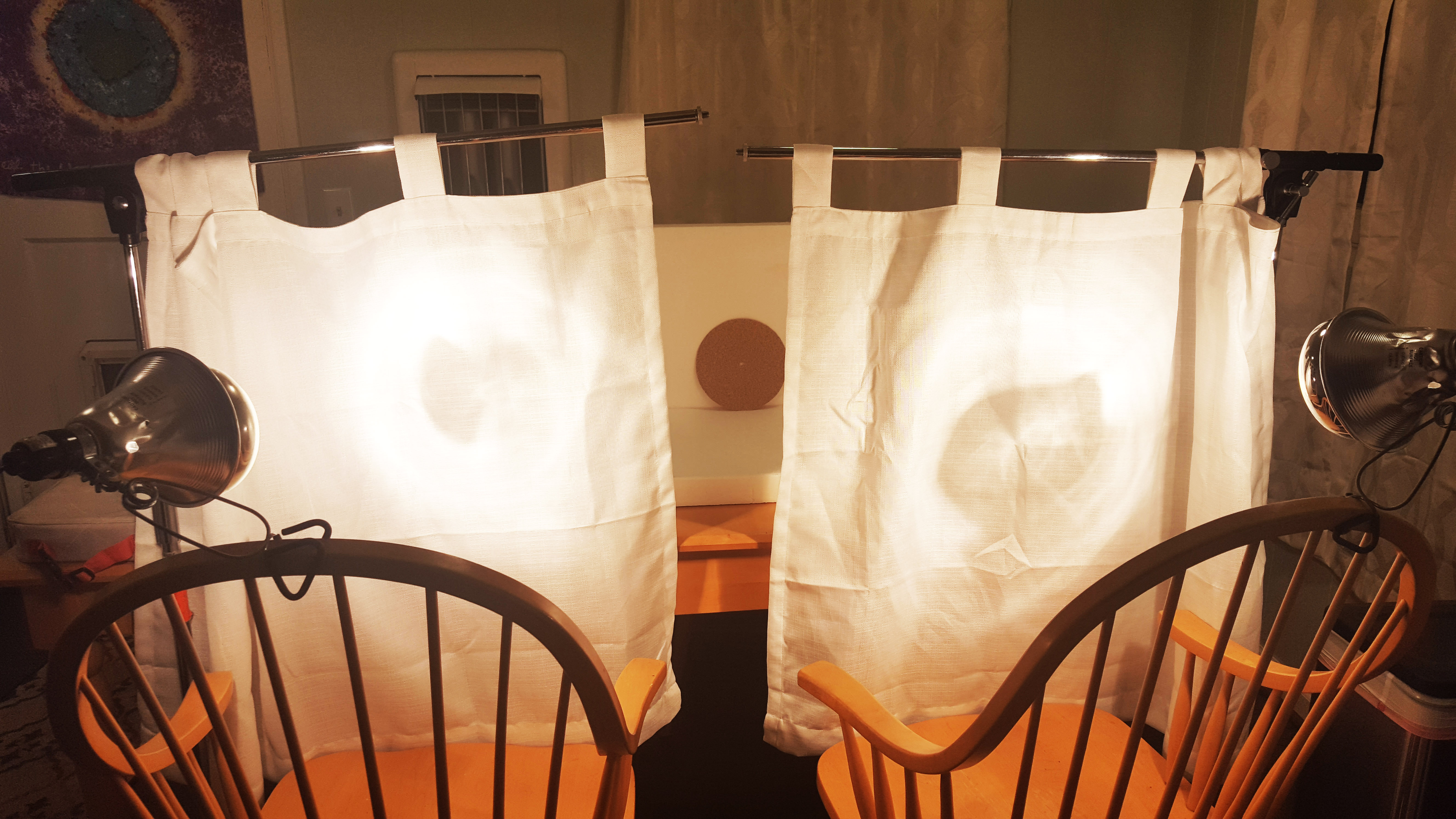

All that was left at this point was a few pictures of the physical release. I took a 7″ record sleeve and cut the piece of sandpaper down to the size of a booklet. Then, I used another piece to create a proper disc. The pictures were taken using the setup that I use to photograph everything for Big Name Records.

I created a fake Facebook for the band’s drummer, posted the link on the article’s page on their website, and watched a scant few plays roll in.

I actually think that if this were a real release, it would be genuinely interesting from a conceptual standpoint. The audio would be fully generative (i.e. each playthrough would be a completely unique waveform), but then, to take that concept to the next level and turn it on its head, the differences between listenings would be indiscernible to the listener. While most generative music is done via computer programming, this release would be different, as it would be the result of purely physical processes. The infinite playback of the disc is also noteworthy; there are plenty of releases with run-out grooves where something repeats over and over again at the end of the disc, but I personally have never seen any kind of disc where the entirety of the audio is infinite. Also, as noted in the article, the disc would likely permanently damage the needle of the listener’s record player. The listener would have to make the conscious choice to put their equipment in harm’s way in order to experience the artist’s piece.

The EP, if real, would be construed by many as extremely pretentious, which would make those people angry. Of course, this is the crux of the satire piece. The pretentiousness, however, (in my humble opinion) could be cool provided that the artist had a solid sense of how ridiculous their piece really was and also provided that they had a good sense of humor about it. The release itself would be comedy gold in its own right, and would be a solid of a jab at noise music’s more absurd artists (while also joining the ranks of noise music’s more absurd artists!). As a final note here, I love that it really does sound kind of cool when you listen to it. I absolutely did not expect to feel that way when I first put the sandpaper on the turntable. The playback sounds exactly like how the surface of sandpaper feels.

It has been brought to my attention that it could be helpful if I lay out a short list of all the reasons why I took the time to do this.

Honestly I didn’t consciously think through all of these things before I began, but they were all reasons that I took the time to do this. The simplest explanation is just that it was a fully natural thing for me to do.